PREI’s Dams - Impacts on Settlements, Fish and Recreation

Impacts on human settlement - Powell River Dam

Large hydroelectric dams, while enabling economic development, often come at a cost - displacing people and damaging cultures and livelihoods. The Tla’amin Nation, in a letter to the BC Utilities Commission, described the impact on their people of the original construction of the Powell River dam and paper mill at the beginning of the 20th century:

“The Powell River paper mill for which the water licenses and energy rights were originally granted was built on top of our ancient village of tiskwat at the mouth of what used to be our river which was later re-named in Powell River… Our ancestors were forced from our village, our river was dammed, the salmon habitat and near-shore marine resources were destroyed and our other watersheds were also impacted by diversion of rivers into the reservoir that came to be called Powell Lake.” (Hegus John Hackett, January 28, 2022 letter to the BC Utilities Commission)

____________________________________________________________

Impacts on Human Settlements - Lois and Horseshoe River Dams

Less documentation exists about the social impacts of the Lois and Horseshoe River dams. However, local histories describe the area as once teeming with wildlife and a destination for fishing, trapping, logging, and homesteading. (G.W. Thompson, Boats, Bucksaws, and Blisters: Pioneer Tales of the Powell River Area, 1990; Barbara Lambert, War Brides and Rosies – Powell River and Stillwater, B.C.)

Both the Tla’amin and shíshálh Nations identify this watershed as part of their traditional lands and signed a shared territory agreement in 2011. The shíshálh Nation’s 2007 Land Use Plan states:

“kwékwenis located at the mouth of the Lois River near the western boundary of shíshálh territory is an extensive residential/village site. The area in and around kwékwenis is noted for being a rich source of clams, aquatic and terrestrial plant resources, herring roe, crab and large game including both deer and elk. In addition, chum and coho salmon were caught at the mouth of the Lois River with the extensive and sophisticated stone and wood fish traps located there."

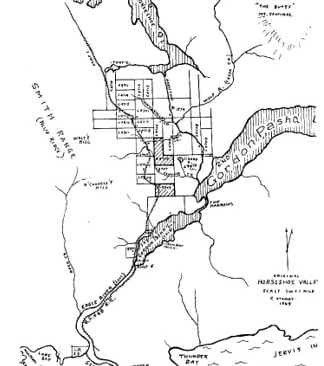

Golden Stanley’s memoirs, Pitlighting Through Conscription, recount his family’s time homesteading in the Horseshoe Valley between 1916 and 1923 on what he described as “some of the best farmland in B.C.” Stanley’s memoirs include a map of the lots homesteaders occupied before they were displaced with construction of the Lois dam.

____________________________________________________________________

Impacts on Fish Habitat

The September 2022 issue of qathet Living describes the impact of dam construction in the qathet area:

“Lois River, Powell River, and Theodosia River were once major spawning grounds for salmon, from the classic red sockeye to the fiery patterned chum. These three watersheds held hundreds of thousands of spawning salmon and were the beginning of life for hundreds of thousands more. That is, before the first dam [at Powell River] was built in 1911… By 1930, the first Lois Lake dam was built and Lois (Eagle) River was blasted…That makes two of qathet’s biggest salmon spawning watersheds dammed and destroyed.”(p. 19, “Where to find qathet’s ghost salmon”, qathet Living, Sept. 2022 https://www.prliving.ca/media/pdfs/Issue2209.pdf)

Key points made in this article include:

Tla’amin oral history recalls massive salmon runs before construction of the Powell River dam, rivaled only by those of the Fraser River.

Spanish explorers described Powell River as the second-largest sockeye stream in the world.

The Powell River dam's height blocks fish passage and makes a fish ladder unfeasible.

The Lois River dam wiped out salmon spawning in six lakes.

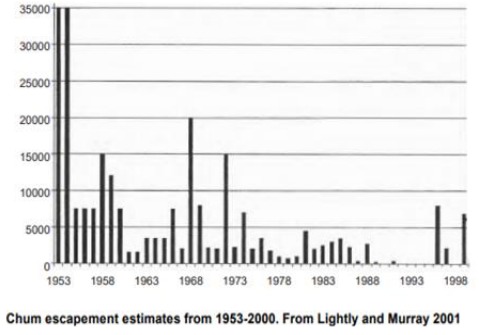

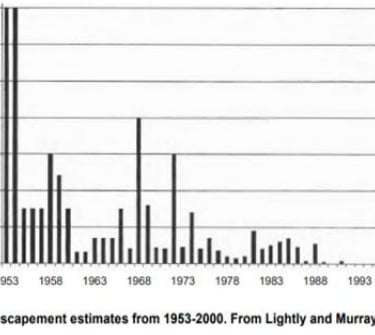

By 2021, Theodosia River chum salmon runs were just 10% of pre-diversion levels.

The “harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat” is prohibited under Section 35 of the federal Fisheries Act unless Fisheries and Oceans Canada grants specific authorization. DFO sets conditions for these authorizations, such as construction of fish ladders.

The Powell, Lois, Horseshoe and Theodosia dams clearly harm fish habitat. However, a search of DFO's public authorization registry found only one relevant permit: the 2021-2035 authorization for "Spill Operations on the Powell River Hydroelectric Project." It may cover aspects such as changes in water flow but would not address the cumulative impacts of the construction of the dam.

All four dams, owned by PREI in the qathet area, were built before 1977 – the year the Fisheries Act was amended to prohibit habitat damage. DFO does not require authorizations for habitat damage caused before that year. However, authorizations are required for any new projects or modifications to existing structures after 1977 that harm habitat. Since PREI’s dams have been modified since 1977, DFO authorizations may exist for those changes.

ED4BC has filed an access to information request with DFO to obtain any such authorizations for dams in the area, which may reveal conditions DFO set to protect fish habitat.

__________________________________________________________

The Theodosia River Diversion: A Case Study in Fish Habitat Loss

As the Powell and Lois dams are so old, being built in the first half of the 20th century, baselines do not exist to show how much fish stocks have changed.

The Theodosia diversion, however, was constructed in 1956 so there are studies documenting the fishery before and after the diversion (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diversion_dam for the difference between a “dam” and a “diversion”).

According to fisheries expert Mark Angelo, before the diversion was constructed Theodosia was known as one of the finest fishing rivers in BC but by 1999 it was listed as the province’s second most endangered waterway.

“The impacts of the diversion were devastating. The river and its fish stocks soon suffered from inadequate flows and the loss of a natural flow regime. The dam also blocked the downstream movement of gravel which resulted in a significant decrease in suitable spawning areas.” (“A dam worth the razing”, Vancouver Sun, April 23, 1999 p. A17)

Angelo recommended that the diversion be removed, pointing out that it not only harmed fish habitat but also was not even that useful for power generation because it did not significantly increase the volume of water available in the Powell Lake reservoir.

The chum fishery on Theodosia has traditionally been a vital food source for the Tla’amin people. The Tla’amin Nation, with financial assistance from PREI, have worked to mitigate the worst impacts of the Theodosia diversion. Their Lands and Resources office has extensive documentation on the ecology of the Theodosia River.

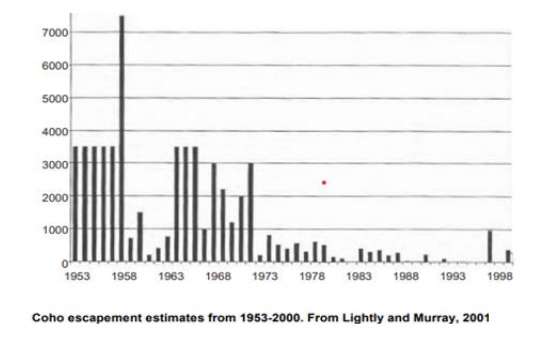

The following charts show how fish stocks declined after the construction of the Theodosia diversion (charts from the study ““Theodosia Watershed Climate Change Impacts and Adaptations Plan”, Theodosia Stewardship Round Table, 2012, courtesy Tla’amin Nation, Lands and Resources)

_____________________________________________________________

Other Environmental Impacts of Dams

While hydro is often considered a “clean” energy source, the ecological footprint of dams is substantial.

As summarized by Earth.Org (https://earth.org/dams-economic-assets-or-ecological-liabilities) major impacts include:

Fragmenting rivers and disrupting their natural flow which threatens the survival of aquatic fauna, especially migratory species.

Directly or indirectly causing soil erosion, species extinction, sedimentation, and waterlogging.

Providing feeding grounds for methane-producing microbes in the sedimentation that builds up in reservoirs. Methane is a greenhouse gas that significantly contributes to climate change.

Blocking nutrients from reaching downstream areas.

Speeding up evaporation of water resources by creating reservoirs with greater surface area than the rivers that are dammed.

_____________________________________________________________________Impacts on Recreation

A 30-mile lake existed before the dam was built at Powell River. According to a 1912 newspaper account, the dam raised the water of the lake by fifteen feet (“Licenses for Submerged Area of Powell Lake”, The Vancouver Daily Province, July 10, 1923, p. 17). Since then, it has been extensively used for boating, swimming, houseboats, and cabins. The lake was promoted in 1924 as having an “enviable record” for trout fishing (“Model Industrial Settlement at Powell River”, Victoria Daily Times, July 5, 1924, p. 13).

However, dramatic fluctuations in water levels in recent years (see section on water levels) have harmed some recreational uses of the lake, with the docks of cabin owners at times being unusable with droughts and water being drawn down for power generation.

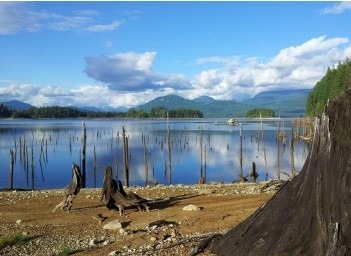

The impacts of the Lois dam on recreation have perhaps been even more negative. The mill’s construction of the dam “drowned the shoreline trees 20 to 40 feet inland and left them to die. Some are still standing like spars, most have fallen into a tumble of silver logs that make the water’s edge all but inaccessible.” (“Splitting shakes”, Vancouver Sun, August 14, 1976, p. 42

______________________________________________________________Impacts of Fluctuating Water Levels

The reservoirs behind hydro dams act like huge batteries, where the level of water stored can be lowered or raised to take advantage of the prevailing price of electricity. PREI used to have long term power purchase agreements with the owners of the paper mill (see the section “A brief history…”) creating a relatively steady demand for power. But with the closure of the mill in 2021, PREI began exporting all the power generated from local dams to markets in the US, with the possible impact that water levels in the Powell and Lois watersheds may vary more widely with changes in the price of electricity.

While being able to adjust how much water is stored and how much is used for power generation at any one time is an economic advantage for hydro producers, extensive and rapid fluctuations in water levels can have negative impacts. When water levels are too low, fish habitat can be destroyed and recreational users can have difficulty boating or reaching their cabins. When water levels are too high, recreational sites can be flooded and wildlife negatively affected such as when beavers have to abandon their dams due to flooding. And when too much water is spilled too rapidly from a dam, this can also wipe out fish habitat.

Along with the problem that driftwood poses to recreation in the Lois watershed, when water is drawn down to generate power during dry periods this can create hazards for boating and can even make it impossible to use sections of the canoe route from Lois to Powell Lakes.

A Simon Fraser University story map for the Horseshoe Valley (https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/51a87148847a4e9aa11a5f64213d4e1a) reported in 2024 that:

“The valley is home to some endangered species such as the northern goshawk, marbled murrelet, winter wren, and the band-tailed pigeon. While these species are at risk due to a number of reasons, dams and frequent logging in the area can exacerbate these issues. There are a number of other sensitive species in the region as well such as fish, beavers, aquatic animals and insects that depend on the freshwater ecosystem that can be impacted by logging and dams in the region.”

One way that wildlife is impacted is the rapid change in water levels depending on how much water is being used to generate electricity. Beaver dams are frequently submerged when water levels are high and areas become impassable for aquatic animals when water levels are low. Marshes that are home to particular species of birds and animals can become damaged by either lower-than-normal or higher-than-normal water levels.

______________________________________________________________Need to Add Conditions to Water Licenses

PREI’s water license for the Theodosia River grants the provincial Water Comptroller the power during low water periods to order the company to adjust water levels “at any time when, in the Opinion of the Comptroller of Water Rights, this release of water is considered to be required in the public interest.”(Water license C113357, 1952)

But all of PREI’s other water licenses currently contain no such provision to protect the public interest. Their license for Powell and Goat lakes dates from 1924 and is less than a page long, in contrast with modern water licenses that can contain many pages of obligations imposed on the license holder in exchange for gaining rights to water. The only obligation that PREI's water licenses impose - aside from the one for Theodosia - is that the company continues to generate electricity. There are no obligations imposed to protect fish habitat or other requirements.

BC Hydro has programs to mitigate the harmful impacts of its dams. These mitigation efforts are sometimes required by their water licenses but also sometimes undertaken voluntarily by the corporation.

Golden Stanley's map of homestead lots before the families were displaced by the Lois dam

Charts show the dramatic decline in chum and coho stocks in the Theodosia River after it was diverted

Low water levels on Powell Lake impact boaters and cabin owners

The Lois dam flooded the forest along the shorelines of Lois and Khartoum

Driftwood hazard on Horseshoe Lake. Water licenses can have conditions requiring dam owners to address driftwood problems, but PREI's do not.

ed4bc@shaw.ca

© 2025. All rights reserved.